The History Behind Maid Cafes

When strolling through Akihabara in Tokyo, it's impossible to miss the colorful signs for “maid cafés” or the cheerful maids in cosplay-style uniforms inviting passersby to step inside. For many Westerners, maid cafés symbolize a quirky blend of Japan's anime, cosplay, and otaku culture. Yet, beyond the modern glitz and playful charm lies a fascinating history that spans centuries. From the humble teahouses of the Edo period to the lively cafés of the early 20th century, maid cafés are the latest evolution of a long-standing tradition of hospitality, entertainment, and cultural adaptation.

This article takes you on a journey through time, uncovering how Japan's tea-serving beauties of the Edo era paved the way for café waitresses, hostesses, and finally, the maids of today’s Akihabara. Let’s start our exploration by stepping back to the streets of Tokyo during the Edo period.

Edo Period (1603–1868): The Mizuchaya (水茶屋)

During the Edo period, many mizuchaya, or teahouses, opened along the roads. In the beginning, they were very simple shops with just a reed screen and served tea and some small traditional desserts. When it came to the middle Edo period (say, ~1750 in Edo and possibly earlier in Kyoto), to be competitive, many teahouses had beauties serving tea. Many men would be attracted to the teahouses because of a beautiful tea maid and would pay around twice the price for tea. Some were even willing to pay 20 times the price at normal teahouses!

Kasamori Osen (1751-1827) was one of those tea maids. She started to work for her family business in the Kagiya teashop near Kasamori Inari Shrine in Yanaka when she was 14. Due to her extreme beauty, many customers came to the teahouse just to see her. As her popularity grew, writers and many Ukiyo-e artists started to depict her in their works. She gained quite some fame and then disappeared when she was 19 years old, leaving only her father in the teahouse. The male customers were so disappointed that they said “A tea kettle has become a medicine pot.” It is said that she married a Shogun guard. Today, there is still a monument for her in Yanaka.

Here are some artworks depicting Kasamori Osen. For example, the famous Suzuki Harunobu has this artwork below, where Osen is located in front of the torii entrance and turning from her admirer.

Of course, many teahouses also evolved into intermediaries between customers and prostitutes. But this is another story that I might cover in future articles.

Early 1900s: Café Waitresses (女給)

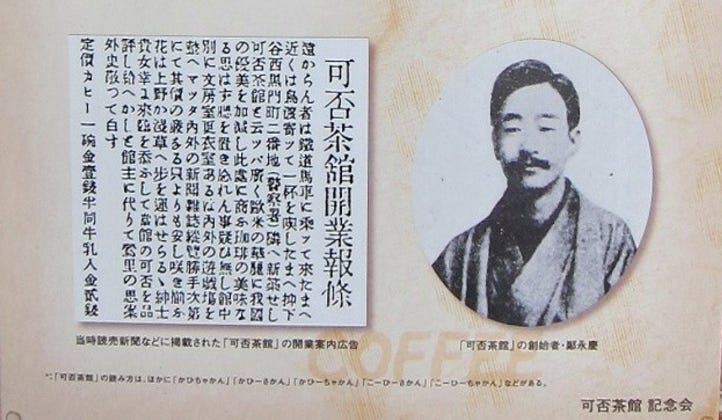

To begin with this period’s story, I want to first mention this interesting transition from teahouses to Cafés. During the Meiji period (1868-1912), coffee was popularized in Japan. Previously, Japanese people were aware of this bitter and dark thing that Dutch people drink, but they were not big fans of it. They had to advertise it as if it was some herbal medicine for health. But when it came to the Meiji period, coffee became popular. The first coffee shop was opened by Nishimura Tsurukichi, called Kahi Chakan (可否茶館). By the way, fun fact—Nishimura also had a Chinese name, Tei Ei-kei, or 鄭永慶. He was related to the famous Koxinga, or 鄭成功 in Chinese. Even today, you can still go to Ueno and find a little site saying this was the site of Kahi Chakan. For people who are interested in the history of coffee in Japan, I recommend doing this little expedition when you visit Tokyo. See Map. I also recommend the book Coffee Life in Japan by Merry White, if you are interested in Japan’s culture of coffee (I will refer to her work for this section as well).

Let’s refocus on café waitresses. As more and more cafés were open for socializing venues around the turn of the century, competition again led to the hiring of pretty girls who could pour coffee and talk to the customers. Beyond serving food and beverages, those café waitresses were expected to engage in polite conversation with the right amount of flirtation, enhancing the café's welcoming atmosphere. These flirtations became bolder and bolder as time went by (especially after the opening of Café Tiger). Those cafés also began to serve alcohol and play jazz music. In Hayashi Fumiko’s autobiographical novel Diary of a Vagabond, she depicts her life working in a café where alcohol is also served. She mentions that a customer tells her: "Try drinking ten glasses of King of Kings. I bet you 10 yen!" Since those cafés were so different from the traditional cafés that just serve coffee, the traditional cafés had to rename themselves as “pure café” or “純喫茶.”

As for the salary, it was not much and the waitresses had to count on the tips for their living. Usually, the mistresses were tipped 1 yen per time of service by the male customers (One gallon of milk is ~0.8 yen).

Despite the fact that the waitresses still catered to a majority of male customers, these positions also gave women opportunities to be in touch with the fast-evolving public realm. As cafés were indeed hubs for interesting conversations and frequented by customers of various careers, café waitresses sometimes served as models for books and movies. As White collects in her book, Tanizaki Junichiro’s novel Naomi, Kazuo Hirotsu’s Jokyuu, and Takeda Rintaro’s Ginza Hacchome are all examples. Moreover, many women who grew into famous public figures worked as café waitresses before. The aforementioned Hayashi Fumiko, who wrote about her experience working at a café in Diary of a Vagabond, later joined Pen Corps and became a quite controversial reporter (as her writings were pro-militarism). Another famous female writer, Sata Ineko, published "Restaurant Rakuyo," which described her experiences as a waitress at a café and was highly praised by Kawabata Yasunari. She was a prominent figure in the proletarian literature movement and focused on women's issues. Especially in the aforementioned "Restaurant Rakuyo," she vividly depicts the struggles of working-class women, particularly those in low-paying and often exploitative jobs. Her experience working as a café waitress very likely gave her some inspiration and helped with her realistic writing.

In the 1930s, Police Departments started to crack down on the café-bars. Regulations for Controlling Special Restaurants and Bars were enacted, where special restaurants and bars were defined as "a restaurant or restaurant with Western-style facilities where women serve and entertain customers." Obviously, it referred to those café-bars. Then, during WWII, due to import restrictions and cultural shifts against Western goods, coffee itself became less popular.

Post-War Era: Hostess Clubs

After WWII, Hostess clubs evolved from pre-war café-bars, cabarets, and dance halls. Entertainment districts such as Ginza and Akasaka became hubs for hostess clubs. They catered primarily to the influx of American GIs and the emerging Japanese business class, as Japan’s economy grew fast. Its direct origin was the "Oasis of the Ginza", opened in November 1945 in the basement of the Matsuya Ginza department store by the Special Comfort Facilities Association's cabaret division. It was established for the occupying forces.

Hostesses’ roles were largely similar to Café waitresses’ roles, with several caveats. First, using “café” as a camouflage was no longer necessary, those new establishments were more like Western nightclubs. According to the Act on the Control and Proper Management of Entertainment and Amusement Businesses in 1948, those venues that entertain customers and provide food and drink, cabarets, waiting rooms, restaurants, cafés, and other facilities were now permitted. Second, girls were often dressed in Western clothes instead of kimonos. And in terms of the work content, Allison described in her book her work experience in a club called “Bijo” in the 80s. her work included “light customers' cigarettes and pour their drinks” and there were three prohibitions “don't smoke, don't rest your elbows on the table, don't put your hands in your pockets in front of customers.”

Interestingly, as the economy thrived in the 60s and 70s, salarymen often went to clubs to socialize with their workplace friends. The environment of those clubs seemed to help solidify group identity and hierarchy among coworkers. Drinking and socializing in a liminal, semi-private space fostered camaraderie and trust among coworkers. This mirrors the environment of the cafés in the 1920s — it was not purely about the sexual relation between the men and the women, but sometimes more about the males bonding with each other.

![Amazon.co.jp: 化身 [Blu-ray] : 黒木瞳, 藤竜也, 阿木燿子, 淡島千景, 三田佳子, 東陽一: DVD Amazon.co.jp: 化身 [Blu-ray] : 黒木瞳, 藤竜也, 阿木燿子, 淡島千景, 三田佳子, 東陽一: DVD](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JOgy!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc090d158-33db-408c-999e-935b8300d0b3_1771x2061.jpeg)

By the way, during this time, host clubs, where men serve women customers, also started to emerge. It began in the 1950s in a small scale, but today, host clubs are everywhere.

Hostess clubs are still in place today (though they underwent quite a lot of reform and evolution. Big nightclubs were replaced by small-scale bars). Nowadays, the hourly pay for the hostesses is around 5000 yen (33 USD) per hour. If you are interested in the nightlife in hostess clubs and how salarymen socialize by going to hostess clubs with their workplace friends, I recommend the book Nightwork: Sexuality, Pleasure, and Corporate Masculinity in a Tokyo Hostess Club by Anne Allison.

2000s until now: Maid Cafés

A new form of entertainment appeared as Japan entered the 2000s (or is it that new?). Maid cafés became popular in Japan in the early 2000s, with the first recognized maid café, Cure Maid Café, opening in Akihabara, Tokyo, in 2001. These cafés gained momentum due to their association with Akihabara's otaku culture, attracting fans of anime, manga, and video games.

Cure Maid café is known for its elegant and subdued Victorian-inspired atmosphere. Staff dress as maids provide polite, graceful service, adhering to a nostalgic and sophisticated concept reminiscent of European aristocratic households. Cure Maid Café serves a menu of teas, light meals, and desserts. It also collaborates with various animes (you can see this on its website), catering to both otaku culture enthusiasts and casual visitors seeking a unique and relaxing experience.

Just as how café waitresses changed during the 1920s, maid cafés also evolved into something more playful. As maid cafés gained popularity, they leaned into fantasy-based interactions. Maids began calling customers "master" and offering playful services like drawing on omelets with ketchup, playing card or video games, and performing dance routines. The variety also expanded. Variants such as school-themed cafes, tsundere cafés (maids acting cold at first and warming up later), and more, emerged. Many maids have become so popular that they even joined idol groups. For example, at-home café has made the first maid idol group.

Moreover, nowadays, not only men frequent those cafés but women customers also visit them. For example, there are quite a lot of girls online posting their experiences in the at-home cafe. Instead of calling girls master, maids would call them my lady (お嬢様). Of course, butler cafes with only male butlers (instead of maids) also showed up. For example, Swallowtail Butler Café is one of them.

As maid cafés became popular, maids also started to appear in other venues. For example, a maid taxi has been introduced in Kanazawa City. Customers can talk, play video games, or watch DVDs in the car with a maid. According to the website, most customers are men in their 30s.

The hourly pay in maid cafés is around 2000 yen (13 USD) per hour in Tokyo. The maids could work part-time in many of those cafés, so students might take those jobs as well.

Some Concluding Thoughts:

Many people think that maid cafés are purely products of the anime culture after the 1990s. However, it could be traced back to as early as the Edo period in the 1700s.

First, the slow evolution from a purely traditional Japanese style to a more Western style shows Japan went from a closed country to a country that integrates various global elements. What people find entertaining reflects the cultural changes in Japan.

Second, the changes and constants of women’s role in public spaces like teahouses, cafés, bars, and nightclubs also reflect changing gender norms, expectations, and agency in Japanese society. Although often exploited, women sometimes got rare opportunities to interact with intellectuals and professionals, thereby helping them improve their social mobility and participate in public spaces. Emerging host clubs and butler cafes for women also symbolize a divergence from the traditional gender role.

Lastly, the history of adult entertainment also illuminates the history of economic trends in Japan. The commercialization of adult services often goes hand-in-hand with economic booms, as people have extra money to entertain themselves. As demand for coffee and alcohol went up, cafés had to compete by hiring pretty waitresses. The purchase of positional goods like opening an expensive bottle of champagne with a club hostess also reflects the economic boom, as people seek to distinguish themselves in a wealthier society. Furthermore, the consumption of high-quality coffee and alcohol implicitly stemmed from international trade as well.

Today's maid cafés, while distinctly modern, represent the latest chapter in centuries of Japanese hospitality traditions. When you visit those maid cafés and enjoy their elaborate parfaits and omurice, don’t forget that you are participating in a tradition that has continuously adapted to reflect Japan's changing relationship with the world, gender roles, and economic development - a living testament to the dynamic nature of Japanese culture.

During my time in Tokyo I went to 2 maid cafes and was pleasantly surprised. They are definitely ready to deal with foreigners, and are incredibly forgiving.

I didn't know maid cafes had such a long history. I thought they were just made by otaku's.