Some Facts About Chinese Local Governments' AI Policy

There’s now plenty of information online about U.S. AI policy, but relatively little about China’s. This can lead to an overly simplified view of China as either a copy of the United States or a copy that doesn’t care about AI safety. To get a better sense of China’s approach, I downloaded all 173 local government AI regulatory policies from PKU Law and recorded which topics and industries each policy covers.1 I find three main facts:

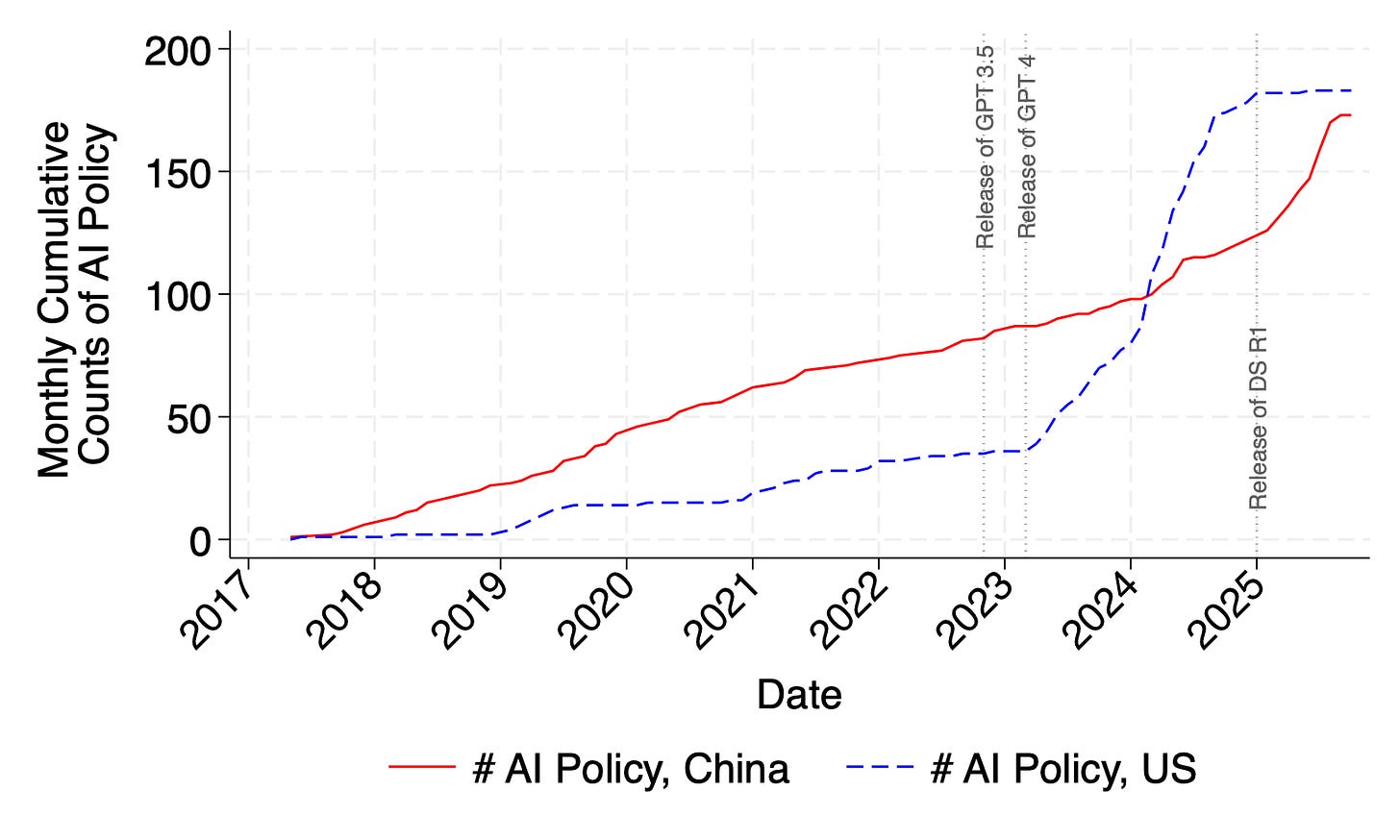

While U.S. state activity visibly ticked up around the releases of GPT-3.5/4, Chinese local AI policymaking rose more steadily and then accelerated around the release of DeepSeek R1.

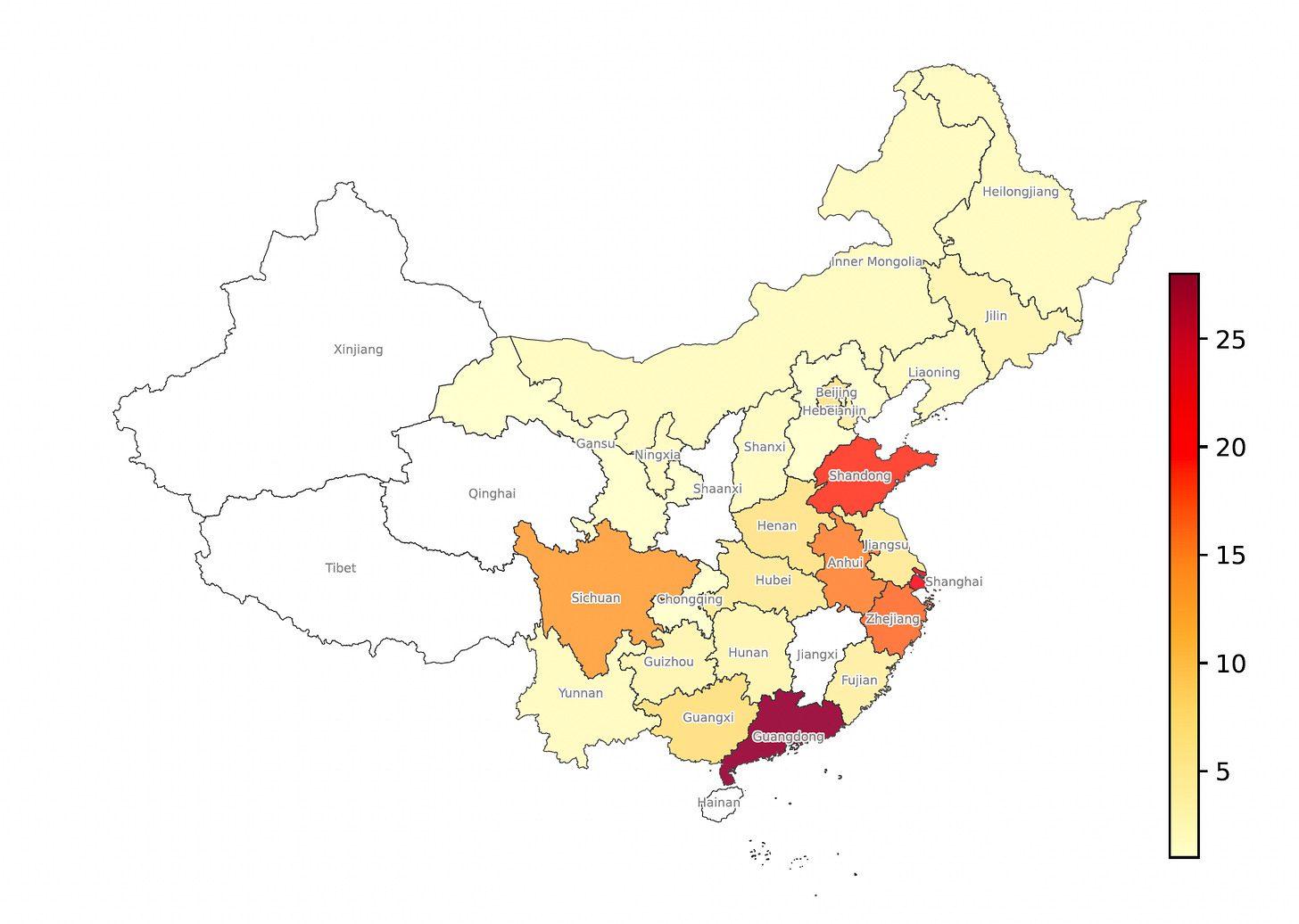

Most Chinese policies cluster in Shandong, Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Anhui, and Sichuan, indicating an uneven provincial development that likely reflects pre-existing economic capacity and AI ecosystems.

Local rules emphasize sectors where AI is readily deployable or labor-substitutable (research, IT, manufacturing), alongside a notable push on education aimed at smoothing labor market adjustment and guarding against equity concerns.

The Number of Policies

First, the cumulative number of local government AI policies in China has been steadily increasing. Looking at Figure 1, there was a slight slowdown from 2021 to 2023, and the pace picked up around 2025.

I also downloaded AI policies of U.S. state governments from the AI Governance and Regulatory Archive (AGORA)2. Note that, as stated on its website, the data is neither comprehensive nor representative, so please take it with a pinch of salt. Nevertheless, I find this trend very close to my expectation: there was a visible, rapid increase in the number of U.S. policies around the release of GPT-3.5 and 4.

Comparing the two, China did not have this increase around the release of GPT-3.5 and 4. Instead, it slowly increases its number of local policies over the years. Why is that?

I have two tentative hypotheses here. First, China ended its zero-COVID policy on December 7, 2022, and local governments were slow to regain their footing. Provinces like Shanghai, Guangdong, and Zhejiang, which usually post strong growth and shoulder much of the country’s AI development later, experienced a marked deceleration in GDP growth early in 2022. The zero-COVID policy’s disruptions appeared to have compressed both supply and demand at once, affecting both commercial activity and household incomes. Given the situation, it’s plausible that these provinces had limited bandwidth to engage with the rapid progress in AI abroad.

Second, ChatGPT.com has been blocked by the Chinese government via the “Great Firewall” since around March 2, 2023. As a result, the “tech shock” did not transmit to the general public as much as it did in the U.S. Thus, there wasn’t a sudden surge of local citizen/firm demand that would force immediate municipal rule-making to regulate. In support of this argument, I do see a slight acceleration in the number of AI policies after the release of DeepSeek R1, when AI became a popular tool in China as well.

Topics of Policies

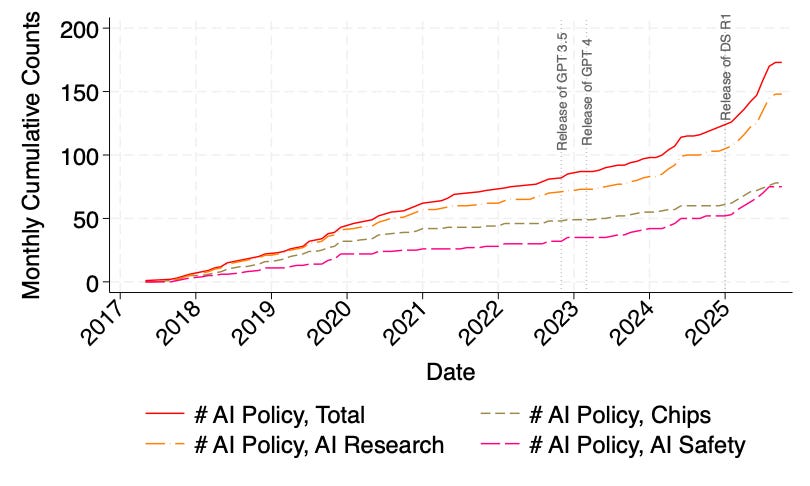

I also analyze the topics of Chinese AI policies. Somewhat contrary to my expectations, local governments seem to mention AI research a lot more than chips when it comes to AI policies.

Another observation is that after the release of DeepSeek’s R1, there was an acceleration in developing policies relevant to AI research, AI safety, and chips, especially in the first two areas. This further shows that DeepSeek’s R1 was the “proto-shock” for Chinese local governments, prompting them to care more about AI development. This is also in contrast to many people’s view that China does not care about AI safety at all.

Probably in response to more policies on AI safety, frontier AI safety research in China has increased rapidly around the same time. As Concordia AI reports, “From June 2024 to May 2025, Chinese scholars published ~26 papers/month, more than double the previous year’s output.”

Industries and Collaboration Fields

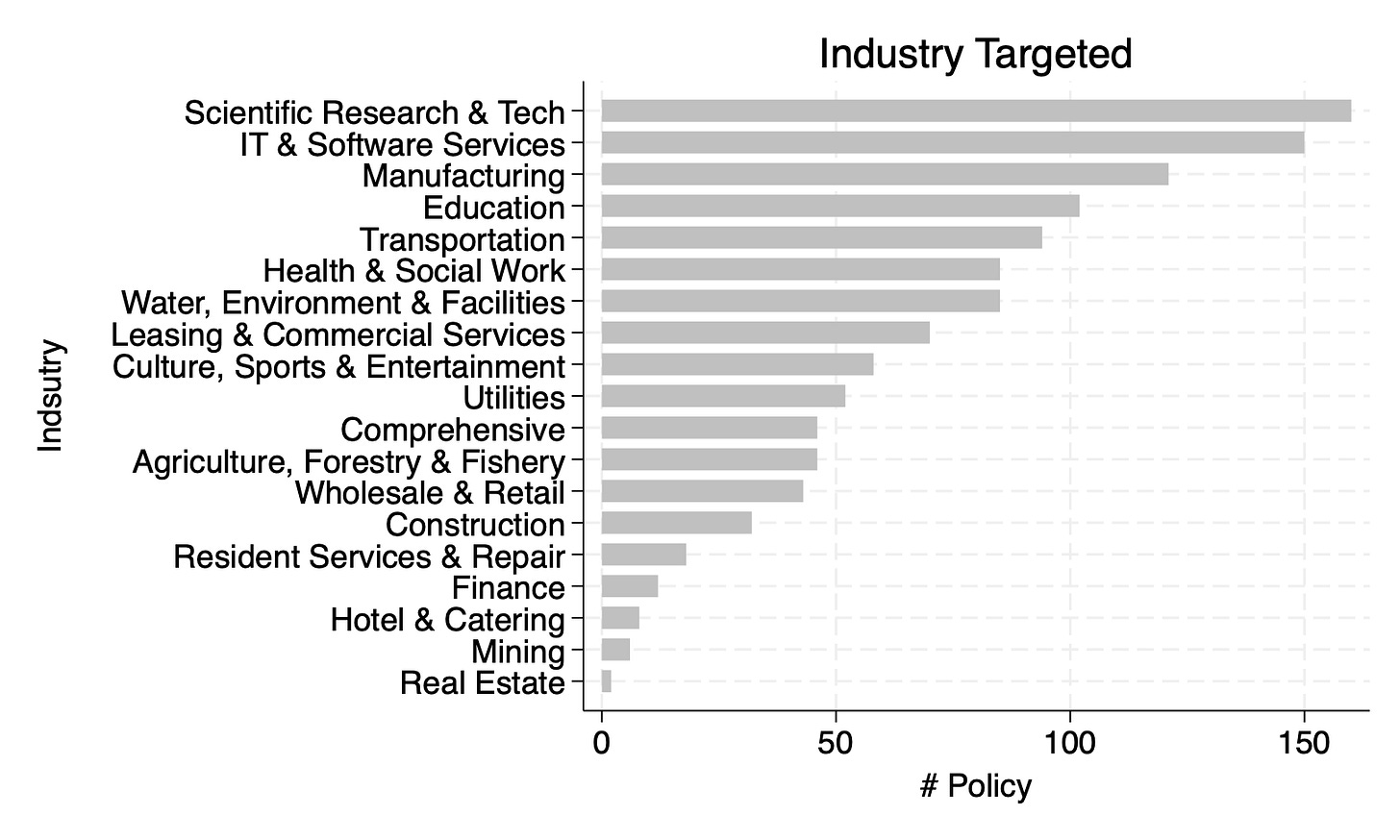

I also check which industries are mentioned as those that can be assisted by AI. Intuitively enough, research, IT, manufacturing, and education are recognized as industries that can be assisted by AI the most. On the contrary, finance, hotel and catering, mining, and real estate seem to be the least targetable when it comes to AI assistance.

Zooming in on the top industries targeted, scientific research and IT make a lot of sense — occupations in these industries are also among those with the highest AI exposure per Eloundou et al. (2023). Manufacturing also makes sense, as it includes AI-assisted cars, robots, and phones.

I find education very interesting. Some provinces have targeted AI education as early as primary and middle school to ensure students can catch up with the new technology. For example, Implementation Plan for ‘Artificial Intelligence + Education’ in Shandong Province mentions “offer general AI literacy courses across all grade levels” and “Achieve system-wide coverage of AI education in primary and secondary schools.” Moreover, Zhejiang Provincial Higher Education Teachers’ Artificial Intelligence Literacy Framework (Trial) takes a step further to talk about AI ethics in education, stating:

Fairness ethics requires teachers to understand fairness issues arising from algorithmic bias and safeguard the rights of vulnerable groups. Benefit ethics requires teachers to ensure that technology applications serve the fundamental goals of education, guard against technology abuse, and avoid ignoring ethical requirements due to a focus on benefits.

I think the focus on education comes from two places. First, the government worries about unemployment stemming from AI replacing labor. Familiarizing students with AI has become increasingly important to prepare them for the job market. Second, Chinese tradition places a strong emphasis on equality in education. People are concerned that AI could further educational inequality between families of different social statuses.

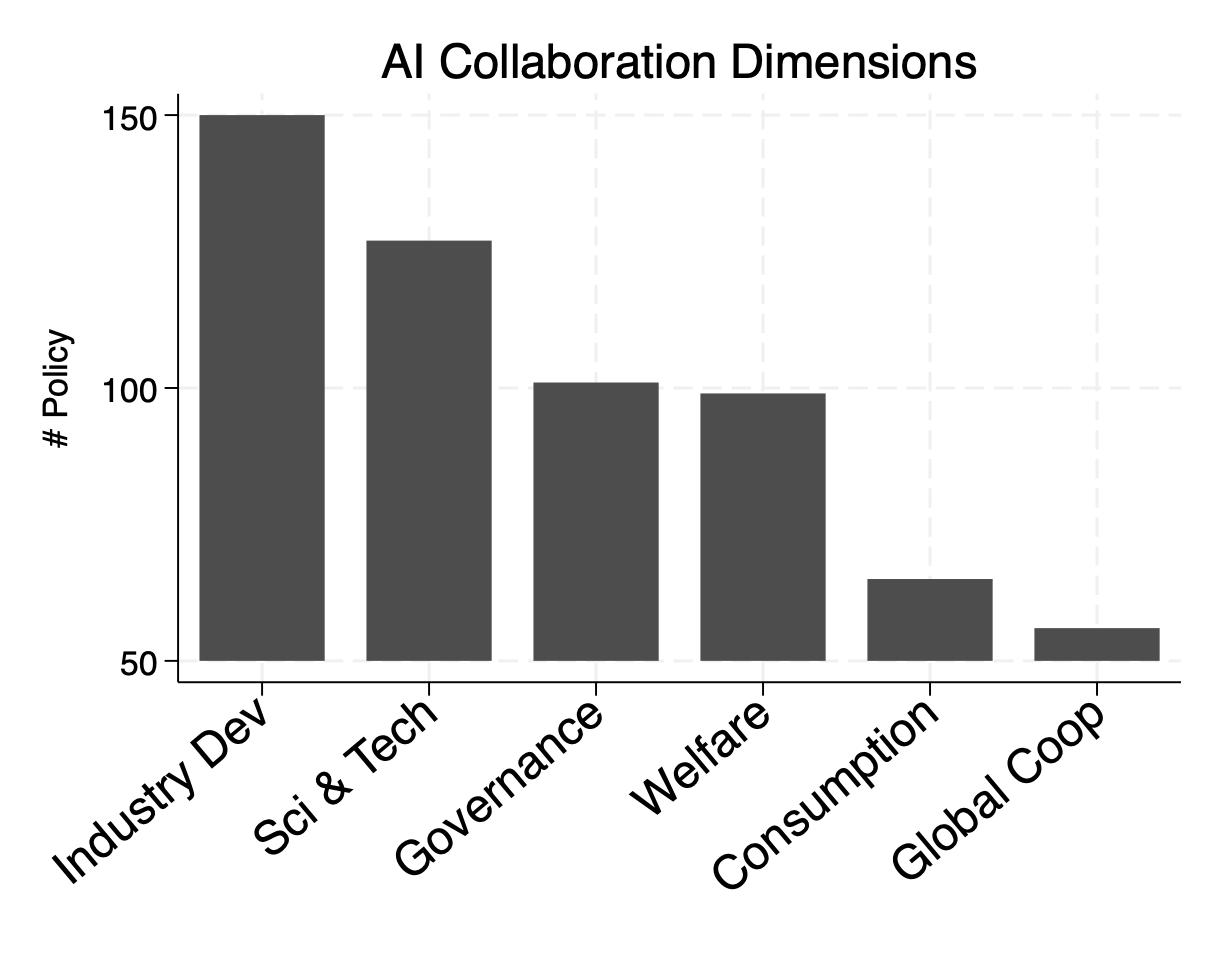

Lastly, moving to fields where AI can be used for collaboration, I use the six fields outlined in the Opinions of the State Council on Deepening the Implementation of the ‘Artificial Intelligence+’ Initiative (2025).

We see that most policies mention industry development and science & technology as potential fields of collaboration. By contrast, increasing the quality of consumption and global cooperation are mentioned less.

Conclusion

China’s local AI governance appears to respond more to domestic market demands than global AI progress milestones. The spatial concentration also means there could be deepened unequal AI development (and its spillovers to other industries) in the country in the future.

I hope these facts help people think about the U.S.-China arms race not as two identical players in a prisoner’s dilemma, but as two players, each with their unique conditions and situations, trying to achieve their unique economic and political goals.

Note that I only analyze those in the category of local regulations and local regulatory documents. I do not include local work documents because those are usually not part of the formal hierarchy of laws and regulations. After downloading, I call the GPT-5 API to analyze them, recording what topics or industries each policy touches on.

I only look at the number of enacted policies.

I found your insight on China's local AI policies pushing education for labor market adjustment and adress equity concerns to be quite pragmatic. But how much of that is truly for human equity versus purely state control?